About three million visitors tour Yellowstone National Park’s 3,440 square miles each year.1 Most come to see natural wonders like Old Faithful and Mammoth Hot Springs, which we featured in our part one article.2

About three million visitors tour Yellowstone National Park’s 3,440 square miles each year.1 Most come to see natural wonders like Old Faithful and Mammoth Hot Springs, which we featured in our part one article.2

But this park packs in much more. Yellowstone has its own grand canyon, waterfalls, and even upright petrified trees. Its surface features look young and testify to the catastrophic forces that shaped them.

Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone

A deep canyon with three waterfalls cuts through the eastern spur of the park. This Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone flows for 20 miles and reaches 1,200 feet deep. Before an ancient catastrophe carved the canyon, hot waters moved upward through gray and red volcanic rocks. This hydrothermal action turned them yellow and orange. These yellow stones line the canyon’s walls and inspired the park’s name and overlook names like Inspiration Point. When did these geologic events occur?

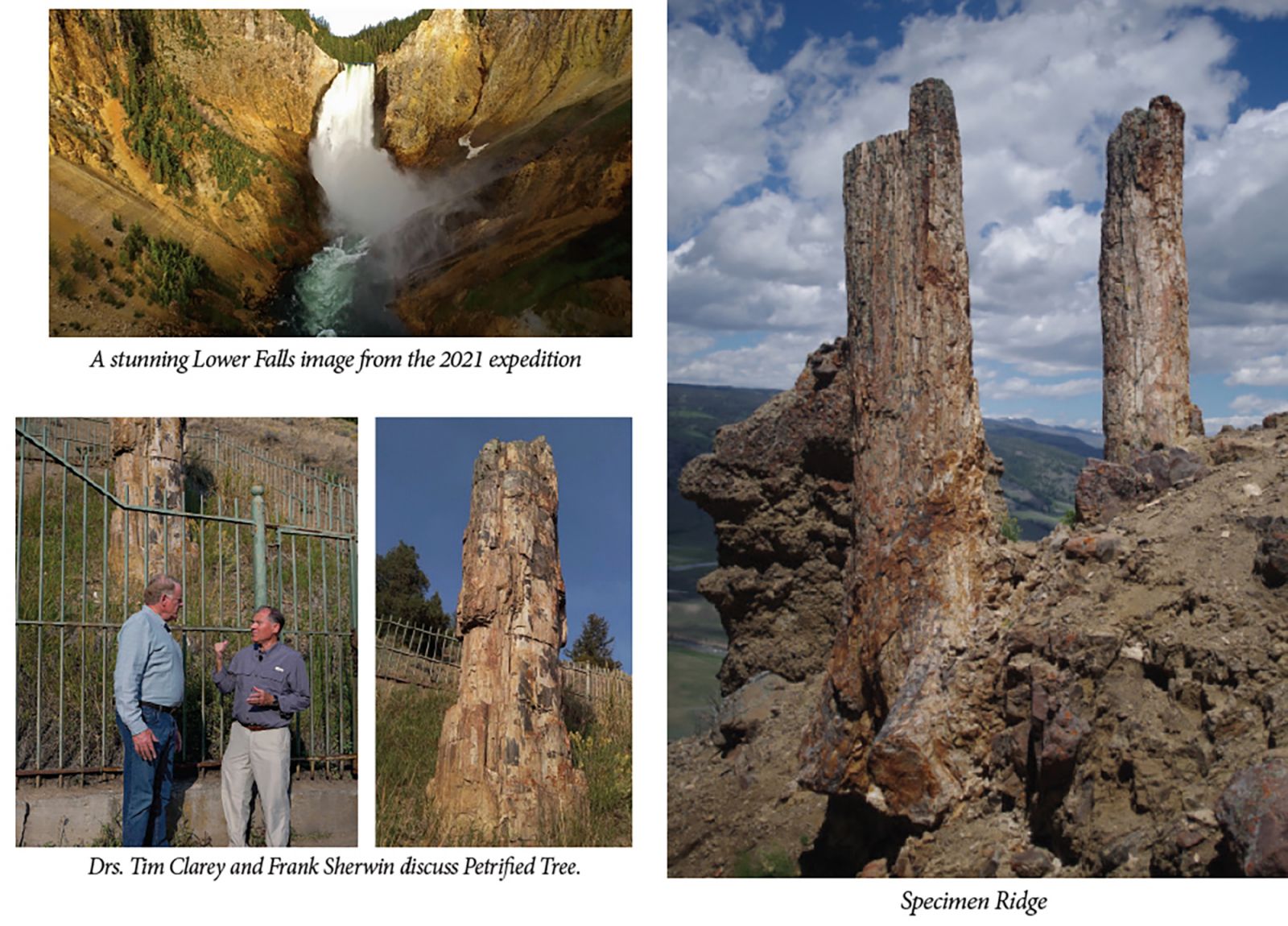

Water flows from Yellowstone Lake through the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone over stunning waterfalls. The first cliff forms Upper Falls, dropping a modest 109 feet. Next, the water plummets 308 feet down Lower Falls. Tower Falls’ 132-foot drop comes last at the northern end of the canyon.

Conventional geologists believe an Ice Age glacier dammed up a huge lake where Yellowstone Lake is today. When water burst through melted ice, it quickly carved through the rock layers.3 However, they also believe this river canyon started to form much earlier—about a half million years ago.4

Roaring water can erode even hard volcanic rock in a short time. It forms tiny vacuum bubbles that implode with great force in a process called cavitation, which can demolish rock or concrete.5 After over a half million years, these three waterfalls should have smooth, gentle slopes instead of the steep-sided falls that today command visitors’ attention. With Yellowstone’s landscape looking only a few thousand years old, it fits well with an Ice Age right after Noah’s Flood.6

Fossil Tree Trunks and Catastrophe

The northeastern part of the park has petrified tree trunks embedded in volcanic rock debris. A hike up Specimen Ridge reveals some of them. About 20 different layers in the vicinity contain tree fossils, many standing vertically. Sycamore, walnut, chestnut, oak, maple, redwood, and magnolias were fossilized here.4 Conventional geologists claim these trees grew in place and that over 20 separate eruptions covered as many separate forests over eons.4 If so, then where are the roots and branches? Instead, some process stripped, sorted, and reburied these tree trunks.

Lessons from the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption offer a more fitting model. That historic blast snapped off a forest of trees at their roots, tore off their branches, and then dumped their trunks into Spirit Lake. Some became waterlogged and sank, thickest end down. They landed upright in the volcanic debris at the lake bottom.7 An even grander catastrophe must have razed, stripped, and interred the many petrified trees at Yellowstone.

The Flood’s world-destroying violence had the energy to do this. Patterns of rock layers globally and around Specimen Ridge suggest these trees sank soon after the Flood crested on Day 150 (Genesis 7:24). Floodwaters likely ripped them from the high hills. As floodwaters flowed off Earth’s surface, they jostled the logs in a moving debris mat. Some tree trunks settled vertically, and some sank faster than others. All the while, Yellowstone’s eruptions trapped the trunks in wet volcanic debris and ash. The 20 different layers would have quickly formed one right after the other.

It’s a tough hike to Specimen Ridge, but visitors can save their legs by taking a turnout to see Petrified Tree. This big tree grew when Noah was alive around 4,500 years ago. It was torn free by the waves, and the Flood buried it. Later, groundwater deposited minerals inside the wood to petrify it.8

Yellowstone’s striking canyons and waterfalls showcase a recently carved landscape. Upright petrified tree trunks make stories of multiple forests sound improbable. And the park’s clear evidence of the catastrophic forces that shaped it testify to the global Flood recorded in Genesis.

References

- Tweit, S. J. 1999. Yellowstone. In America’s Spectacular National Parks. L. B. O’Connor and D. Levy, eds. Los Angeles, CA: Perpetua Press, 76-79.

- Clarey, T. and B. Thomas. 2022. Yellowstone National Park, Part 1: A Flood Supervolcano, Acts & Facts. 51 (3): 10-13.

- Clarey, T. 2017. Minuscule Erosion Points to Hawaii’s Youth. Acts & Facts. 46 (1): 9.

- Hacker, D. and D. Foster. 2018. Yellowstone National Park: Northwest Wyoming, Eastern Idaho, Southern Montana. In The Geology of National Parks, 7th ed. D. Hacker, D. Foster, and A. G. Harris, eds. Dubuque, IA: Kendall-Hunt, 765-791.

- Morris, J. 2011. The Channeled Scablands. Acts & Facts. 40 (10): 15.

- Hebert, J. 2018. The Bible Best Explains the Ice Age. Acts & Facts. 47 (11): 10-13.

- Austin, S. A. 1986. Mt. St. Helens and Catastrophism. Acts & Facts. 15 (7).

- Thomas, B. and T. Clarey. 2021. The Painted Desert: Fossils in Flooded Mud Flats. Acts & Facts. 50 (4): 16-19.

* Drs. Clarey and Thomas are Research Scientists at the Institute for Creation Research. Dr. Clarey earned his Ph.D. in geology from Western Michigan University, and Dr. Thomas earned his Ph.D. in paleobiochemistry from the University of Liverpool.