Animals don’t laugh, smirk, roll their eyes, or give subtle squints like humans do. Hundreds of different tiny facial expressions can convey our thoughts and feelings in an instant—all using the human face. But faces do more than express. They hold sensors for sight, smell, sound, temperature, and humidity. They also keep sun and dust out of those sensors, and they enable us to breathe, eat, speak, and sing. Each person’s face does all this while looking unique among billions of others. How did our marvelous faces get here?

Animals don’t laugh, smirk, roll their eyes, or give subtle squints like humans do. Hundreds of different tiny facial expressions can convey our thoughts and feelings in an instant—all using the human face. But faces do more than express. They hold sensors for sight, smell, sound, temperature, and humidity. They also keep sun and dust out of those sensors, and they enable us to breathe, eat, speak, and sing. Each person’s face does all this while looking unique among billions of others. How did our marvelous faces get here?

A team based at Arizona State University (ASU) Institute of Human Origins recently speculated on how the distinct features of human faces evolved from ape-like faces.1  Their science-sounding terms masked a failure to face certain facts that should have framed their conclusion.

The team needed to imagine how natural processes could have transformed a chimpanzee-like face into a human’s. This may sound like no big deal until one begins to list the many differences. Here are a few face features that Darwinists need natural selection and mutations to somehow expertly craft in just a few million years:

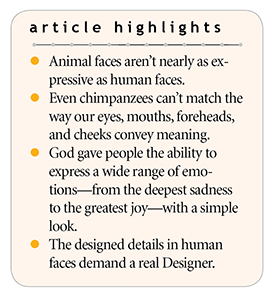

- 20 muscles. Humans have about 20 more facial muscles than modern chimpanzees.2 Their combinations of contractions craft a cornucopia of communication.

- Smooth skin. Even men with thick beards have smooth skin in spaces where apes have furry faces.

- Eyebrows. Look close—chimps have no hairy eyebrows.

- Visible sclera. Only human eyes have the whites showing in such a way that we can communicate merely using eye motions.

- Nose bridge. Apes have no bone for their nose.

- Smaller ears. Humans have smaller ears than apes.

- Lower cheekbones. The distance between teeth and cheekbones is shorter in humans than in primates.

- Lips. Apes’ closed mouths hide that soft red tissue that human lips have on constant display.

Good luck restructuring all that biology with nothing but a series of random mutations. And that’s just the facial differences.

Completely unfazed by the fact that no scientist has seen natural selection craft a single such feature—let alone something akin to the entire suite listed here—ASU News wrote, “Changes in the jaw, teeth and face responded to shifts in diet and feeding behavior.”1

In other words, our ancestors’ facial traits supposedly changed at least partly in response to what they ate. Even today, human faces look different when we eat raw and unprocessed food.3 But this happens when innate sensors detect intense chewing pressures and internal workings interpret that stress and then activate jaw bone and muscle growth during childhood development. Most of us process our food at least partly by hand, giving us smaller mouths. These adjustments have nothing to do with evolution and everything to do with ingenious, adaptable design.

No measurements from past faces document these researchers’ speculated shift from ape to man. Instead of science, they rely on blind faith in evolutionary dogmas such as that expressed by ASU paleoanthropologist William Kimbel, who asserted, “We are a product of our past.”1

Unscientific speculations—popular though they may be—should never substitute for observable, repeatable science. What experiments affirm ape-to-man evolution? For that matter, no science so far refutes the words of Jesus, who said, “But from the beginning of the creation, God ‘made them male and female’”…with expressive human faces right from the start.4

References

- Russ, J. The history of humanity is in your face. Arizona State University News. Posted on iho.asu.edu April 15, 2019, accessed May 3, 2019.

- Gregory, W. K., ed. 1950. The Anatomy of the Gorilla. The studies of Henry Cushier Raven, and contributions by William B. Atkinson and others. A collaborative work of the American Museum of Natural History and Columbia University. New York: Columbia University Press, 17.

- Thomas, B. Human Jawbone Size Reflects Diet, Not Just Lineage. Creation Science Update. Posted on ICR.org January 3, 2012, accessed May 20, 2019.

- Mark 10:6.

* Dr. Thomas is Research Associate at the Institute for Creation Research and earned his Ph.D. in paleobiochemistry from the University of Liverpool.