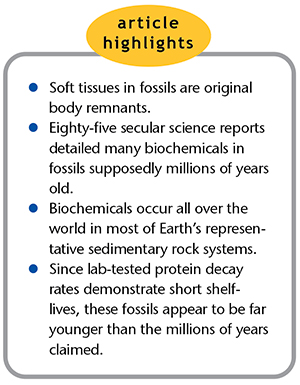

In December 2019, the journal Expert Review of Proteomics published a paper I authored with Stephen Taylor titled “Proteomes of the past: the pursuit of proteins in paleontology.”1 The article features a table that lists 85 technical reports of still-existing biomaterial—mostly proteins—discovered inside fossils.

In December 2019, the journal Expert Review of Proteomics published a paper I authored with Stephen Taylor titled “Proteomes of the past: the pursuit of proteins in paleontology.”1 The article features a table that lists 85 technical reports of still-existing biomaterial—mostly proteins—discovered inside fossils.

Can proteins last millions of years? Not according to decay rate measurements. Five incriminating trends emerged from these 85 secular reports. Our review sharpens the tension between how short a time biochemicals last and the supposed age of the fossils that contain them. We wrote:

Collagen decay rate experimental results build a temporal expectation that restricts bone collagen to archeological time frames, yet many reports of collagen and other proteins in older-than-archeological samples have sprinkled the paleontological literature for decades. Tension between the expectation of lability [susceptibility to chemical breakdown] and observations of longevity has fueled steady debate over the veracity of original biochemistry remnants in fossils.1

The 85 reports included descriptions of original skin, connective tissues, flexible and branching blood vessels, bone cells, and probable blood cells. Original biochemistry includes tattered but still-detectable osteocalcin, hemoglobin, elastin, laminin, ovalbumin, PHEX, histone, keratin, chitin, possible DNA, collagen, and collagen sequence—all inside fossil bones.

The first trend we found noted biomaterials from all kinds of different fossilized animals, not just dinosaurs.2 Thus, researchers need not restrict their searches for fossil biomaterials to any specific plant or animal type.

The second trend from all of these reports, which span over a half century of exploration, found no better preservation in one ancient environment over another. Whether living in air, oceans, lakes, swamps, or forests before they were fossilized, fossils could still contain biomaterials.3

Third, a bar graph of the number of relevant publications per year showed an increased interest in this field within the last two decades. Additionally, Figure 5 from our paper plots discoveries onto a world map to show that biomaterials in fossils occur virtually worldwide. We predict that future investigations could discover original biomaterials wherever fossils are found.

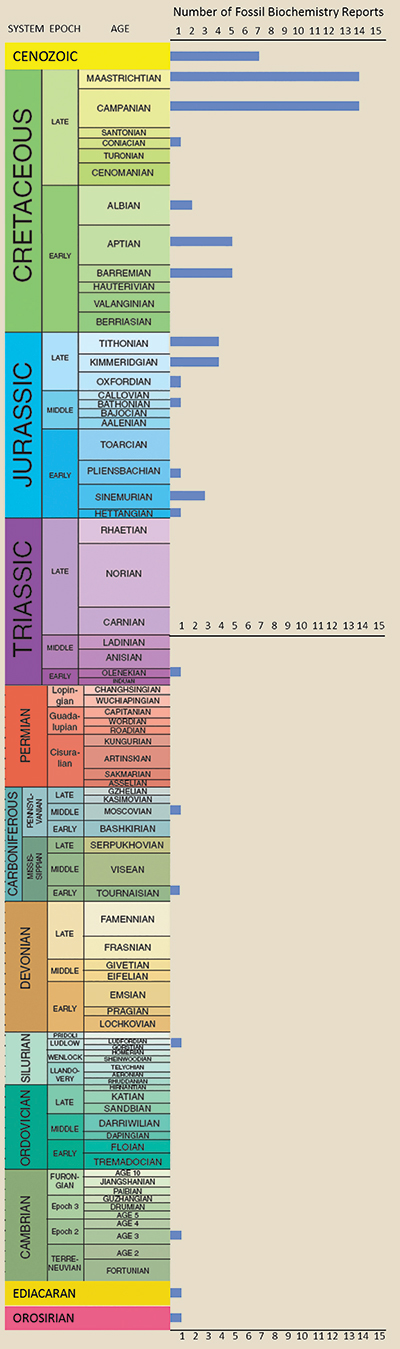

The fifth and final trend presents the biggest obstacle for those who insist that rock layers represent vast eons. We found reports of original biomaterials from seven of the 10 standard geologic systems plus one report each from the Precambrian and Ediacaran layers—the bottommost sediments on Earth. As one of our anonymous peer reviewers protested in response to these findings, having biomaterials last over 70 million years—let alone 500 million—is simply fantasy.

Proteins decay relentlessly and relatively fast. Yet protein discoveries keep piling up. Thus, “it is likely that contention will persist.”1 Our secular colleagues now have a sharper look at the vast depth and wide spread of young-looking biomaterials from fossils.

References

- Thomas, B. and S. Taylor. 2019. Proteomes of the past: the pursuit of proteins in paleontology. Expert Review of Proteomics. 16 (11-12): 881-895.

- Tissues or biochemistry were reported in dinosaur, eggshell, turtle, bird, marine worm casings, sponge, clam, mosasaur, tree, insect, arachnid, frog, salamander, and crinoid fossils.

- “Fossilized” does not necessarily mean “mineralized,” as this list clearly shows. Fossils include remains of once-living things that were totally replaced by minerals, partly replaced by minerals, mineralized only in tiny pore spaces, or not mineralized at all—like natural mummies.

* Dr. Thomas is Research Associate at the Institute for Creation Research and earned his Ph.D. in paleobiochemistry from the University of Liverpool.