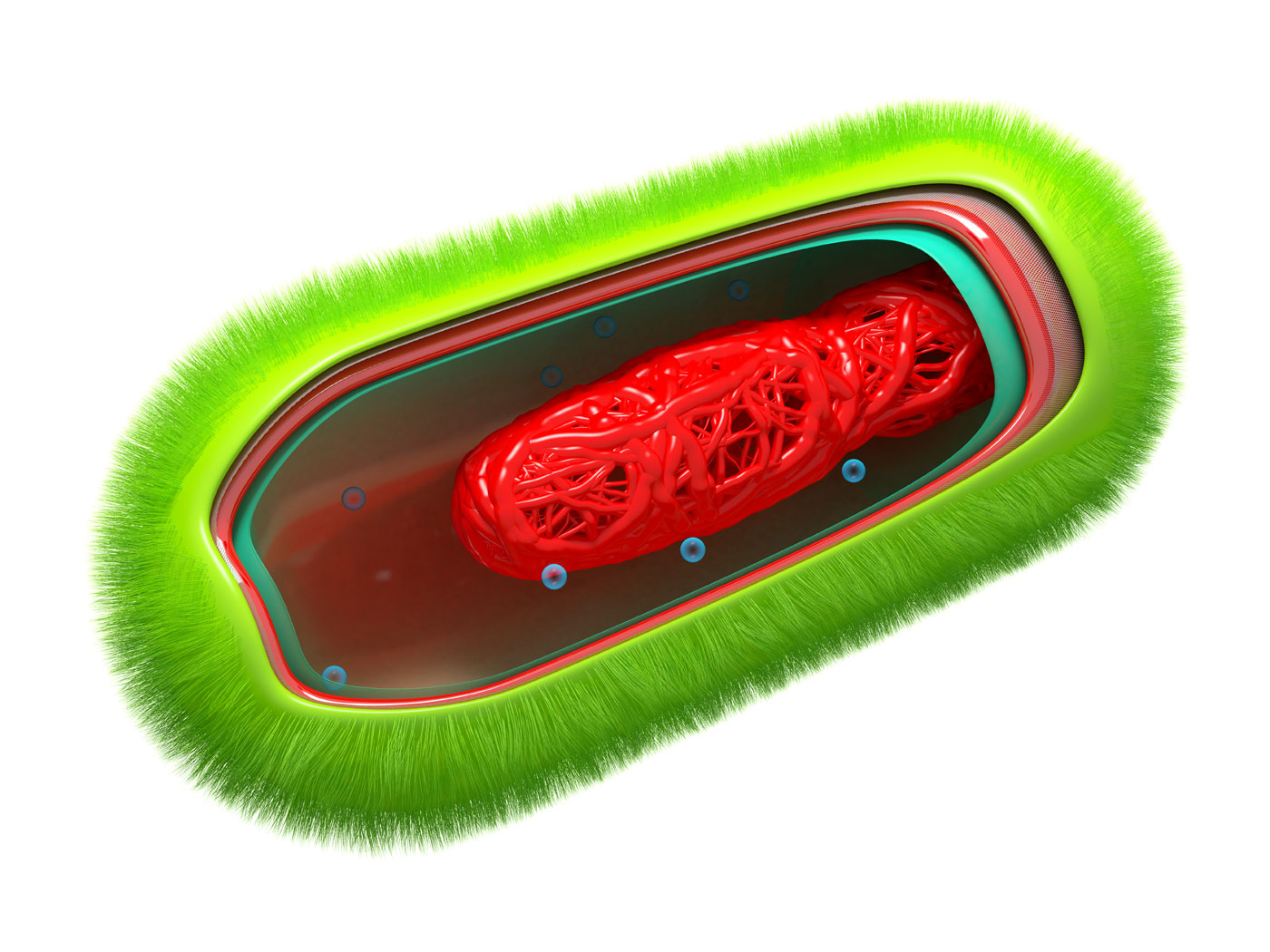

Fossil experts from University College Cork in Ireland took stunning images of Psittacosaurus skin. The dinosaurs’ belly shows patches of skin that glow orange under UV light. However, the top of this dinosaur’s tail has long fibers that many assume were feather-like bristles. So, these study authors suggest that since this dinosaur had two types of skin, perhaps the evolutionary ancestors of today’s birds did, too. Do this fossil’s details really help solve the riddle of feather evolution?

Psittacosaurus was smaller than most dinosaurs. This specimen was excavated from the Jehol Biota of China. It is unique in that silica seems to have directly replaced bits of its skin. Regional volcanics added silica to the wet sediments that quickly buried the creature. A nearby shrimp fossil emphasizes the watery burial. Silica from volcanics famously replaced logs to make Arizona’s Petrified Forest National Park. So, we knew that dissolved silica could replace wood, but not skin.

Perhaps this skin-turned-glass can clarify the feather evolution story for us. After all, senior author Maria McNamara told University College Cork, “The evolution of feathers from reptilian scales is one of the most profound yet poorly understood events in vertebrate evolution.”1

“Profound” may be an understatement. Feather evolution would have required new sets of building instructions. One set would construct the feather follicle, presumably shouldering aside the scaly skin building programs if indeed this happened in some dinosaur. Then, specialized cells would have to have emerged within that follicle to manufacture and export keratin, the main feather building material. Those cells would then need instructions on how to deposit the keratin in the precise shape, size, length, and direction—starting with the furthest tip of the feather and ending at the base.

Perhaps the reason this “profound” evolution is so “poorly understood” is that nobody has seen it or clear evidence of it, either past or present.

For this particular Psittacosaurus to help fill the feather hole in evolution’s grand narrative, it needs to show that it had both scaly skin and smooth, feather-making skin, like the study authors claim. It turns out that the team, publishing in Nature Communications, could demonstrate only half of that.2

Three independent techniques verified that some of the dinosaur’s skin did indeed have reptilian scales, complete with dark structures called melanosomes, and no follicles. For example, electron microscopy showed thin epidermal layers called stratum corneum, though made of silica. These layers are comparable to crocodile scaly skin. But what about the evidence for feather-evolving bristles? The team found no follicles nor any evidence of supposed feather-making skin!

No evidence? No problem. Simply assert some into existence. The study authors wrote, “It is reasonable to presume that the skin of feathered body regions, i.e. the tail, exhibited some or all of the modifications related to feather support and movement that characterize the skin of extant birds.”2 Well, it’s only “reasonable” if one also presumes that the tail fibers were feathers and that feathers evolved. But even some evolutionists doubt that the Psittacosaurus tail fibers were bristles rather than skin remnants.3

So, do this fossil’s details revive feather evolution? This absence of evidence actually helps bury it. Either it had no undisputed feathers like dinosaurs or it had fully formed feathers like some fossil birds show.

References

- Researchers discover hidden step in dinosaur feather evolution. News and Views. University College Cork. Posted on ucc.ie May 21, 2024, accessed May 28, 2024.

- Yang, Z. et al. 2024. Cellular structure of dinosaur scales reveals retention of reptile-type skin during the evolutionary transition to feathers. Nature Communications. 15, article 4063.

- Lingham-Soliar, T. 2015. The Vertebrate Integument, Volume 2. Berlin, GER: Springer Berlin, Heidelberg, 282.

Stage image: Fossil of Psittacosaurus

Stage image credit: Copyright © Brian Thomas. Used in accordance with federal copyright (fair use doctrine) law.

* Dr. Brian Thomas is a research scientist at the Institute for Creation Research and earned his Ph.D. in paleobiochemistry from the University of Liverpool.