Old-earth geologists claim that observations contradict the Flood model origin for Grand Canyon.1 However, recently exposed sediments at Lake Mead refute their claims and instead fully support the Flood model.

Old-earth geologists claim that observations contradict the Flood model origin for Grand Canyon.1 However, recently exposed sediments at Lake Mead refute their claims and instead fully support the Flood model.

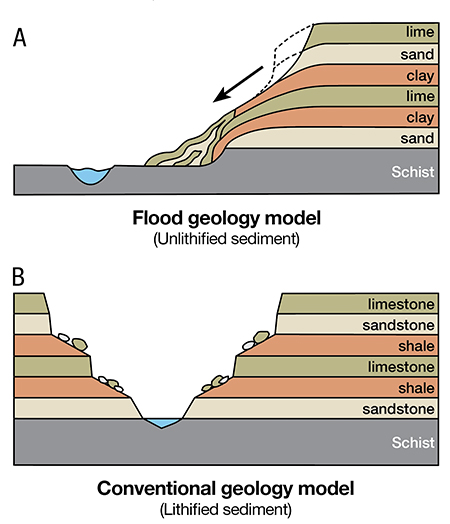

These geologists argue that if the Flood rapidly carved Grand Canyon, the freshly deposited and unlithified (not yet stone) sediment layers should have collapsed, thinned, and slumped into the chasm (Figure 1). In effect, they predict “piles of mixed sediment at the base of the exposed embankments,” with no vertical cliffs.1

They further assert that only fully lithified, ancient rock layers would maintain Grand Canyon’s pattern of vertical cliffs and slopes. They report they have actually observed these processes in today’s world, postulating, “So, what is actually observed? None of the expected features for the flood geology model are observed. All of the expected features from the conventional geology model are observed.”1

It sounds convincing, until we look deeper. Their explanation is a classic example of the straw man fallacy. We don’t actually observe the thinning and slumping they predicted. We only observe the mixed vertical cliffs and slopes of the modern canyon walls, and this clearly doesn’t disprove the Flood model.

Geologists agree Grand Canyon was formed by the removal of about 1,000 cubic miles of sediment and rock.1 The canyon is 277 miles in length. It’s 4 to 18 miles in width and has a depth of over 6,000 feet in some locations.

In 1935, Lake Mead formed behind Hoover Dam, creating a trap for water and river sediment. Fluctuating snow pack and runoff levels caused the lake to drop from its high-water level of 1,225 feet above sea level in 1983 to about 1,080 feet today. A white-colored band—a bathtub ring—visible above the current lake level showcases this drop in water elevation.

As a consequence, the Colorado River has eroded through the former lake sediments at the eastern end of the lake, exposing sandy cliffs 20 to 40 feet high. These cliffs make a perfect test of the Flood model since the sediments consist of unlithified, packed sand and clay just like many of the Flood sediments at the time Grand Canyon was carved.

This past August, I rafted the last 100 miles of Grand Canyon. As I passed the freshly exposed sediments in Lake Mead, I observed firsthand the rapid erosion of unlithified sands and clays that had been deposited over the past 80-plus years.

Amazingly, the exposed lake sediments look like a miniature version of Grand Canyon (Figure 2). There was no mixing of the sediments or thinning of the layers. Instead, we observed vertical sandy cliffs, some sloping layers, and more vertical cliffs. In fact, the cliffs showed frequent cross-bedding and angular unconformities likely caused by lake currents and fluctuating lake levels. All these features match perfectly with what’s observed in Grand Canyon rocks.

The recent “little Grand Canyon” exposed by Lake Mead is exactly what Flood geologists have predicted. Packed, water-deposited sediment will stand vertically even if unlithified. Real observations made in the field, not mere assumptions based on an old-earth worldview, match perfectly with a late-Flood carving of Grand Canyon.2

References

- Helble, T. and C. Hill. 2016. Carving of the Grand Canyon: A lot of time and a little water, a lot of water and a little time (or something else?) In The Grand Canyon: Monument to an Ancient Earth. Tulsa, OK: Kregel Publications, 163-172.

- Clarey, T. 2018. Grand Canyon Carved by Flood Runoff. Acts & Facts. 47 (12): 10-13.

* Dr. Clarey is Research Associate at the Institute for Creation Research and earned his Ph.D. in geology from Western Michigan University.