Erythromycin is an antibiotic that has been prescribed to many of us that may have experienced skin or upper respiratory tract infections. It was discovered in 1949 in a soil sample from the Philippines. The drug is even used in fishcare as a broad-spectrum treatment of bacterial outbreaks in fish populations.

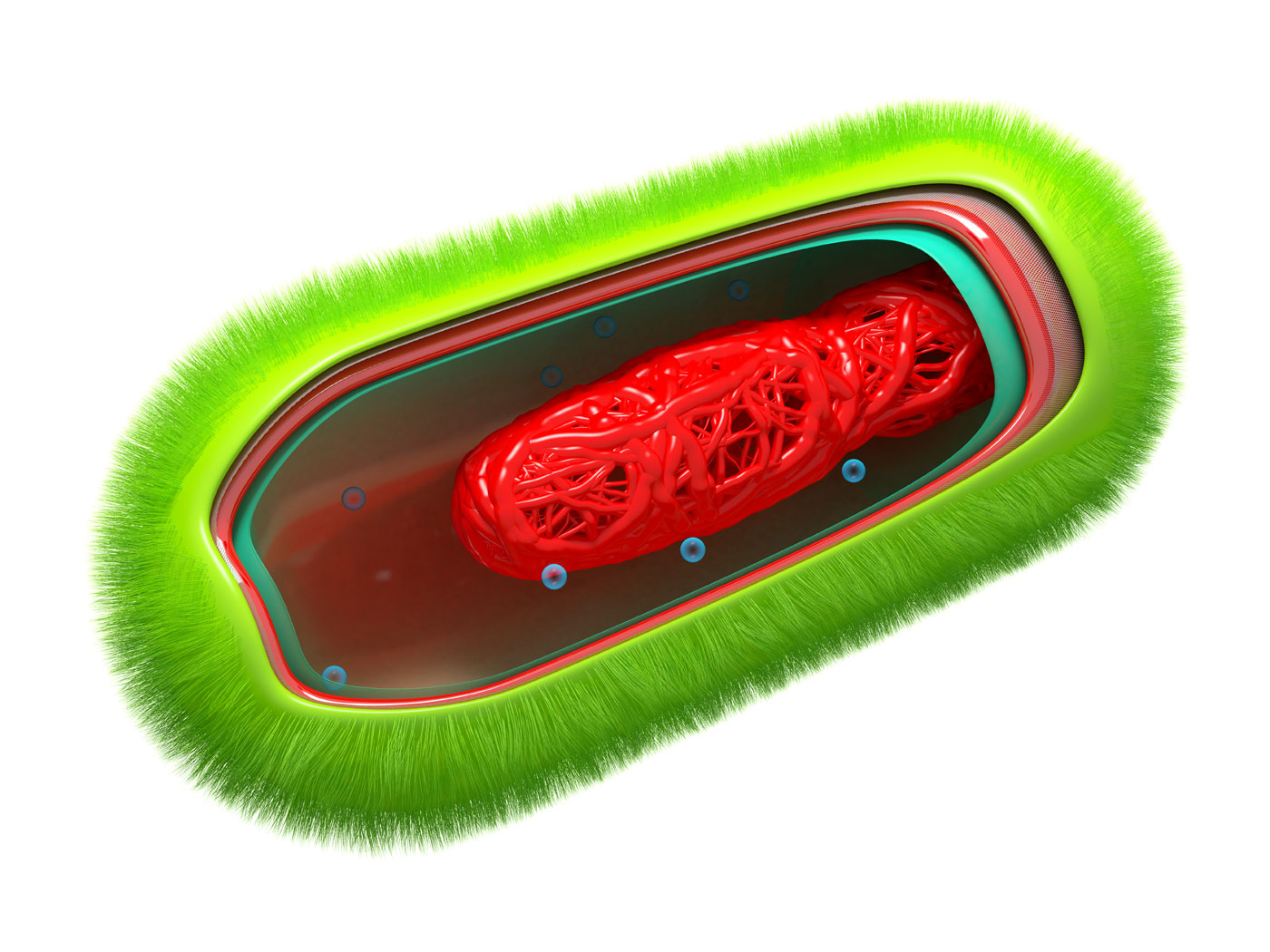

Recently, researchers from the Institute of Oceanology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (IOCAS), have been working with the Asiatic hard clam, Meretrix petechialis, which lives in a mud flat environment.1 These intertidal environments are rich with a wide variety of bacteria, some of which are disease-causing. Even without an adaptive, lymphocyte-based immune system clams (and other invertebrates) proliferate.

Although lacking an adaptive immune system and often living in habitats with dense and diverse bacterial populations, marine invertebrates thrive in the presence of potentially challenging microbial pathogens. However, the mechanisms underlying this resistance remain largely unexplored and promise to reveal novel strategies of microbial resistance.2

Progress in answering this question is seen in the fact that the Asiatic hard clam “can synthesize, store, and secrete the antibiotic erythromycin.”1 The prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences stated,

This potent macrolide antimicrobial [erythromycin], thought to be synthesized only by microorganisms, is produced by specific mucus-rich cells beneath the clam’s mantle epithelium, which interfaces directly with the bacteria-rich environment. The antibacterial activity was confirmed by bacteriostatic assay.2

Creationists are not surprised at this discovery. In order to survive, there must be a way marine invertebrates have been designed by the Creator to avoid bacterial infections.

But evolutionists must posit a naturalistic explanation regarding the origin of this antibiotic, "However, our results suggested that the erythromycin-producing genes in M. petechialis have an origin in animal lineages and represent convergent evolution with bacteria"1 said Prof. Liu Baozhong from the IOCAS.

Convergence, or parallel development, is used by evolutionists to somehow prove evolution. In this case, without explaining either the origin of clams (they first appear in the middle Cambrian “510 million years ago”—as clams), or the origin of the erythromycin-producing genes in M. petechialis, an appeal is made they both simply evolved in parallel. Problem solved.

Regardless, this is a significant discovery because it was previously thought that only bacteria can produce erythromycin. Indeed, first author of the study in the Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, Yue Xin stated, "We also documented erythromycin production in a related species, Meretrix lyrate, which suggests that the antibiotic may be more widely produced by marine invertebrates."1

Again, this is not a surprise from a biblical standpoint. It could be predicted on the basis of the creation model that God has designed a majority of marine invertebrates with an ability to synthesize erythromycin and perhaps other natural antibiotics, ensuring a balanced ecosystem.

References

1. Science Writer. Asiatic hard clams can synthesize antibiotics. phys.org. Posted on phys.org November 29, 2022, accessed November 29, 2022.

2. Yue, X. et al. The mud-dwelling clam Meretrix petechialis secretes endogenously synthesized erythromycin. PNAS. Posted on pnas.org November 28, 2022, accessed December 1, 2022.)

* Dr. Sherwin is science news writer at the Institute for Creation Research. He earned an M.A. in zoology from the University of Northern Colorado and received an Honorary Doctorate of Science from Pensacola Christian College.