Introduction

Introduction

Three main arguments are commonly used to support the Big Bang model of the universe’s origin:

- The apparent expansion of the universe, inferred from redshifted spectra of distant galaxies;

- The fact that the Big Bang can account for the observed relative abundances of hydrogen and helium;

- The observed cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation, thought to be an “afterglow” from a time about 400,000 years after the supposed Big Bang.

Although an expanding universe is consistent with the Big Bang, it doesn’t necessarily demand a Big Bang as its cause. One could imagine that for some reason God imposed an expansion on His created universe, perhaps to keep the universe from collapsing under its own gravity. Of course, this assumes that secular scientists’ interpretation of the redshift data is correct, which some creation scientists are starting to question.1

The second argument isn’t as impressive as it sounds. The Big Bang model is able to account for the observed abundances of hydrogen and helium because it contains an adjustable parameter called the baryon-to-photon ratio. Big Bang scientists simply choose a value for this parameter that gives them the right answer. Even so, it’s not clear that the Big Bang can account for the total number of atoms (per unit volume) in the universe. And even with this adjustable parameter, the Big Bang cannot correctly account for the observed amounts of lithium isotopes.2,3

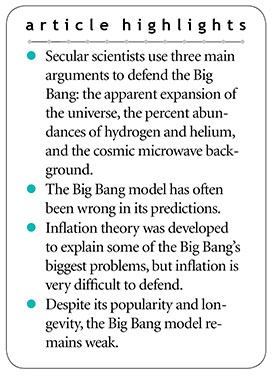

However, the third argument, the existence of the CMB radiation, is a successful prediction of the Big Bang. We observe very faint but uniform electromagnetic radiation—radiation not associated with particular stars or galaxies—coming from all directions in space, and the intensity of this radiation is brightest in the microwave part of the electromagnetic spectrum. Big Bang scientists interpret this to be the oldest light in the universe, light emitted when the universe became cool enough for neutral hydrogen atoms to form. As the universe expanded, the wavelengths of these traveling photons were stretched so that most of them had wavelengths corresponding to the microwave part of the electromagnetic spectrum. The intensity of this CMB radiation (as a function of wavelength or frequency) very closely matches the intensity of the radiation given off by an ideal emitter/absorber that physicists call a blackbody. Such a blackbody would have a temperature of 2.7 Kelvins, or about -270° Celsius (Figure 1).

The CMB and Inflation Theory

Aside from successfully predicting the CMB’s existence, the Big Bang has often been wrong about the CMB’s details. In order to understand why, let’s review some of the Big Bang’s main assumptions.

The Big Bang model assumes there are no special places or directions in space. In other words, it supposes the universe is homogeneous and isotropic. Because the Big Bang assumes there are no special directions in space, any direction should look much the same as any other direction. And because space is supposed to look nearly the same in all directions, the CMB should also look nearly the same in any direction. This is indeed the case. So far, so good.

But Big Bang theorists soon realized that the uniformity of the CMB, even though required by their model, was also a problem for the Big Bang model. Such uniformity would require all points within the supposed primeval fireball to be characterized by the same temperature. Given that the Big Bang was supposedly undirected and purposeless, this requires very unlikely initial conditions. Generally, these theorists don’t like this because it could be construed as fine-tuning, or evidence for a Designer. However, they could also explain the uniformity if radiant energy from one direction in space “warmed up” space in another direction. But this radiant energy travels at the finite (but still very fast) speed of light, and even the 13.8 billion years allowed by the Big Bang model is not enough time for this process to completely equalize the CMB everywhere in the universe. This is known as the horizon problem.4

So, theorists proposed that very shortly after the Big Bang the universe underwent a huge growth spurt called inflation in which space itself expanded faster than the speed of light. Supposedly, the part of the universe we see was, before inflation, small enough that traveling radiant energy did have sufficient time to warm the cool spots. Supposedly, inflation “ballooned” the universe so much that the part of the CMB we can observe is very uniform—as demanded by Big Bang assumptions.

Not surprisingly, there is no direct evidence for inflation. Supposed evidence for inflation made front-page headlines in 2014 but was quickly retracted.5 Moreover, inflation theory has become so strange that even secular cosmologists harshly criticize it.6

Creation scientists have no problem with Earth being near the center of the universe, as this might be expected given God’s great care and attention for this planet. ![]()

A CMB Surprise

According to the Big Bang model, however, the CMB should not be perfectly uniform. Although the Big Bang assumption of isotropy does not allow for temperature differences that stretch across large patches of the sky, it predicts that small patches (with an angular diameter of about 1° or less) should show extremely subtle variations in temperature, with some spots being very slightly warmer or cooler than 2.7 Kelvins.7 Secular cosmologists originally expected the sizes of these temperature differences to be about one ten-thousandth of a Kelvin, but later measurements showed that this expectation was 10 times too large; the actual measured differences were about a hundred-thousandth of a Kelvin.8

Creation astronomer Dr. Danny Faulkner often recounts his personal memory of how surprised secular scientists were when the measured temperature differences were smaller than expected. So, despite popular perception, observations have not always been in agreement with Big Bang expectations. Instead, the Big Bang has often been tweaked to absorb “anomalous” observations.

Challenges for Secular and Creation Scientists

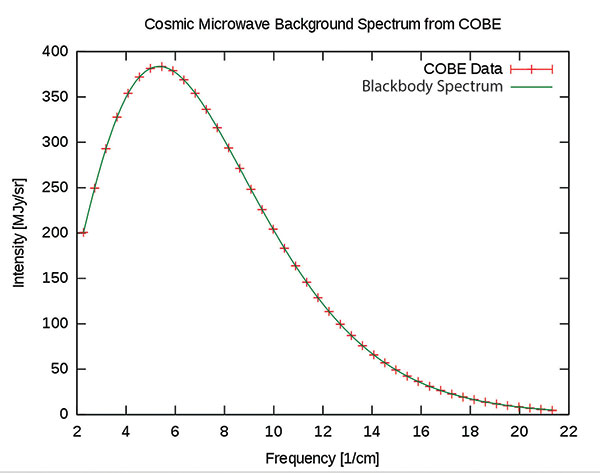

Even so, there are other problems with the Big Bang interpretation of the CMB. Although small-scale (angular diameter of less than 1°) temperature anisotropies (differences) are expected in the Big Bang model, there also exist very subtle temperature anisotropies within the CMB stretching across large patches of the sky. Because the Big Bang assumes isotropy, these large-scale anisotropies should not exist. Secular scientists had hoped that better data would remove these apparent anomalies, but higher-resolution CMB data obtained by the Planck satellite (Figure 2) disappointed them. George Efstathiou, a Cambridge astrophysicist and one of the leaders of the Planck satellite’s science team, explained in an interview:

The theory of inflation predicts that today’s universe should appear uniform at the largest scales in all directions....That uniformity should also characterize the distribution of fluctuations at the largest scales within the CMB. But these anomalies, which Planck confirmed, such as the cold spot, suggest that this isn’t the case....This is very strange....And I think that if there really is anything to this, you have to question how that fits in with inflation....It’s really puzzling.9

To summarize, the Big Bang assumes that the universe is isotropic—space should basically look the same in all directions. Since the universe is assumed to be isotropic, the CMB should also be isotropic. And the CMB is very isotropic, which would seem to be a plus for the Big Bang model. But Big Bang cosmologists realized that isotropy was extremely unlikely, so they proposed inflation to explain why the CMB was isotropic. But there is no evidence supporting inflation theory, and the theory has become so weird that it’s now being harshly criticized by other secular scientists. The small-scale temperature differences in the CMB were about 10 times smaller than predicted, so the Big Bang was tweaked to bring these temperature differences into agreement with the model. But the high-resolution Planck data show that subtle large-scale features in the CMB are present—features that are not supposed to exist if inflation is correct!

But it gets worse. Some of these large-scale temperature differences in the CMB seem to be aligned with our solar system.10 As acknowledged by outspoken Big Bang proponent Lawrence Krauss:

But when you look at CMB map, you also see that the structure that is observed, is in fact, in a weird way, correlated with the plane of the earth around the sun. Is this Copernicus coming back to haunt us? That’s crazy. We’re looking at the whole universe. There’s no way there should be a correlation of structure with our motion of the earth around the sun—the plane of the earth around the sun—the ecliptic. That would say we are truly the center of the universe.11

This apparent alignment, if real, is a huge problem for the Big Bang, as it seems wildly improbable that Earth should be in a special place in the universe. Don’t forget that according to the Big Bang, special places and directions aren’t supposed to exist at all! Creation scientists have no problem with Earth being near the center of the universe, as this might be expected given God’s great care and attention for this planet.

But the CMB also presents challenges for creation scientists since it needs to be explained within a creation context. Recently, Dr. Faulkner and creation physicist Dr. Russell Humphreys both proposed possible explanations for the CMB within a biblical worldview.12,13 However, more work needs to be done in order to refine and decide between competing models.

The scientific case for the Big Bang model is extremely weak, & no one, especially Christians, should feel compelled to accept it. ![]()

Conclusion

The successful prediction of the existence of a cosmic microwave background is arguably the Big Bang’s greatest success, and creation scientists need to provide a detailed alternative explanation for its existence. Even so, there are features within the CMB that are completely contrary to Big Bang expectations. Given that the Big Bang’s strongest argument has these problems, one can safely conclude that the scientific case for the Big Bang model is extremely weak, and no one, especially Christians, should feel compelled to accept it.

References

- Hartnett, J. 2011. Does observational evidence indicate the universe is expanding?—part 2: the case against expansion. Journal of Creation. 25 (3): 115-120.

- Hebert, J. 2013. Dark Matter, Sparticles, and the Big Bang. Acts & Facts. 42 (9): 17-19.

- Thomas, B. Big Bang Fizzles under Lithium Test. Creation Science Update. Posted on ICR.org September 22, 2014, accessed March 7, 2018.

- Coppedge, D. F. 2007. The Light-Distance Problem. Acts & Facts. 36 (6).

- Hebert, J. Big Bang Evidence Retracted. Creation Science Update. Posted on ICR.org February 12, 2015, accessed March 9, 2018.

- Hebert, J. Big Bang Blowup at Scientific American. Creation Science Update. Posted on ICR.org May 29, 2017, accessed March 9, 2018.

- In the 13.8 billion years allowed by the Big Bang model, traveling radiation would only have had sufficient time to equalize the CMB in small patches of the sky (with angular diameters less than about 1°).

- Wright, E. L. 2004. Theoretical Overview of Cosmic Microwave Background Anisotropy. In Measuring and Modeling the Universe, Carnegie Observatories Astrophysics Series, vol. 2. W. L. Freedman, ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 292.

- Discoveries from Planck may mean rethinking how the universe began. PhysOrg. Posted on phys.org July 26, 2013, accessed March 9, 2018.

- Huterer, D. 2007. Why is the solar system cosmically aligned? Astronomy. 35 (12): 38-43.

- The Energy of Empty Space That Isn’t Zero: A Talk with Lawrence Krauss. Edge. Posted on edge.org July 5, 2006, accessed March 9, 2018.

- Faulkner, D. R. 2016. Thoughts on the raqîa‘ and a Possible Explanation for the Cosmic Microwave Background. Answers Research Journal. 9: 57-65.

- Humphreys, D. R. 2014. New view of gravity explains cosmic microwave background radiation. Journal of Creation. 28 (3): 106-114.

* Dr. Hebert is Research Associate at the Institute for Creation Research and earned his Ph.D. in physics from the University of Texas at Dallas.