Sometimes, separating observation from speculation presents a challenge. For example, a recent news report of a possible planet in outer space mixed an observation with ideas of distant planet formation. Does this news coverage provide enough detail to help tease apart what is seen from what was unseen?

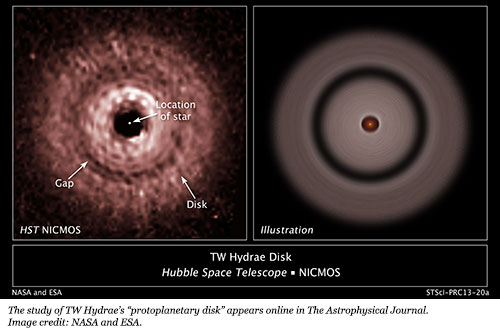

Astronomers used the Near-Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer on the Hubble telescope to image what they called a "protoplanetary disk" in infrared light.1 The TW Hydrae Disk consists of fine particles in a flat, round plane, with a small red-dwarf star in its center. Scientists find fascination in an apparent gap in the distant disk. They propose a planet-like object could be plowing up the debris as it slowly revolves around its star.

Is a gap in a dust disk enough evidence to assert a "protoplanet?" The very name means that planets are forming there, but the mere act of naming is not the same as evidence.

Is a gap in a dust disk enough evidence to assert a "protoplanet?" The very name means that planets are forming there, but the mere act of naming is not the same as evidence.

Even if an exoplanet orbits out there, no scientific rationale suggests that the planet is actually forming, and there are several reasons to think otherwise. In fact, the very NASA news release itself seems to contradict the secular claim of planet formation by a slow and gradual accretion of debris.

First, evolution-based speculations about the timing of planet formation conflict with speculations about when the red dwarf star formed. The red dwarf is supposedly "only 8 million years old, making it an unlikely star to host a planet, according to this theory. There has not been enough time for a planet to grow through the slow accumulation of smaller debris."1 When accounting for its great distance from its star—and that star's tiny size—the possible planet would supposedly have needed two billion years to form!

In contrast to a planet existing for millions of years before its star supposedly evolved, naturalistic planet formation stories tell of stars forming first, so that their gravity could then help planet formation.

In addition, evolutionary models require pebble-sized debris to seed a protoplanet, but the observed gap lies in an area of the disk populated by tiny dust-sized grains.

All things considered, if this distant dust disk does hold an exoplanet, supernatural creation would account for it most sensibly.

From observations in our own solar system, we know that worlds can create gaps in orbiting disks. Saturn's rings, for example, contain several gaps due to the gravitational influence of Saturn's orbiting moons. "It is very feasible that a planet may be the cause of the gap in the disk of TW Hydrae,” said astronomer and Institute for Creation Research Director of Physical Sciences Jason Lisle. “But the notion that such a planet has formed from such material is merely a story."

References

- Harrington, J. D. and D. Weaver. NASA's Hubble Uncovers Evidence of Farthest Planet Forming from its Star. NASA press release, June 13, 2013.

Image credit: NASA/ESA/Hubble.

* Mr. Thomas is Science Writer at the Institute for Creation Research.

Article posted on June 21, 2013.