Nobel Prize-winning German physicist Max Planck perceptively observed that “if you change the way you look at things, the things you look at change.”1 That pithy statement sums up one reason why scientific theories are crafted. Theories shape the way people look at, think about, or understand things in nature.

ICR and other researchers who are developing an engineering-based, organism-focused theory of biological design (TOBD) have a straightforward goal. We want to initiate a much-overdue conceptual catharsis in biological literature. This will involve replacing Darwinian selectionism with a scientifically superior model that’s powerful enough to “change the way” people “look at” biology. This will have groundbreaking benefits.

Benefit 1: Mysticism Out and Objectivity In

Evolutionists saturate their functional explanations with mysticism, with “just so” stories and “phantom breeders [and] ghosts in Darwinism”2 that produce “the kinds of speculative flights associated with Darwinian theory.”3 They employ an elaborate mental construct of imaginative scenarios cloaked in hazy jargon such as selection event (unobserved); unit/object of selection (unidentifiable); selection pressure (unquantifiable); random (untestable); favored, acted on, under selection (personifications); and other ill-defined lingo.

These are crucial concepts to the evolutionary narrative, but they’re not conducive to objective assessments. The conventional selection-based explanation of biological adaptation is not a description of real, observable events or a cause of any phenomena. It’s simply the verbiage Darwinists use to express the concepts underlying their anti-design way of looking at creatures.

An engineering-based approach is invaluable to biological science. Engineers only include quantifiable objects and tangible causes in their explanations. The objectivity of a TOBD improves biology by using engineering-based methodologies to bring objectivity, precision, and clarity to explanations. These are the disciplines biology needs to clean up the misleading concepts of selectionism.

Benefit 2: A Restored Appreciation of Creatures

Scientific theories can have profound theological implications. Darwin shrewdly crafted his theory to point people toward atheism without using derogatory words directly against God. He first changed the way people thought about creatures, which then precipitated into radically changed perceptions about God and life.

Darwin used the phenomenon that people will draw conclusions about the Creator from what they think about creation. He and his followers changed the way people thought about God in an extraordinarily devalued way by writing a new narrative that changed their thinking about His handiwork.

Darwin closed The Origin by summing up his worldview as one that necessitates

a Struggle for Life, and…Natural Selection, entailing…the Extinction of less-improved forms. Thus, from the war of nature, from famine and death, the most exalted object which we are capable of conceiving, namely, the production of the higher animals, directly follows. There is grandeur in this view of life.4

What assumptions underlie this grisly narrative? Selectionism portrays creatures as a hodgepodge of parts that are always incomplete and often broken or vestigial. They get cobbled together from the bottom up without any purposeful intent by the hit-and-miss sorting of random genetic mistakes (mutations) via deadly struggles to survive. No wonder that when people buy into Darwin’s way of looking at creatures, their view of God changes for the worse. If God’s creatures look bad, then God looks bad.

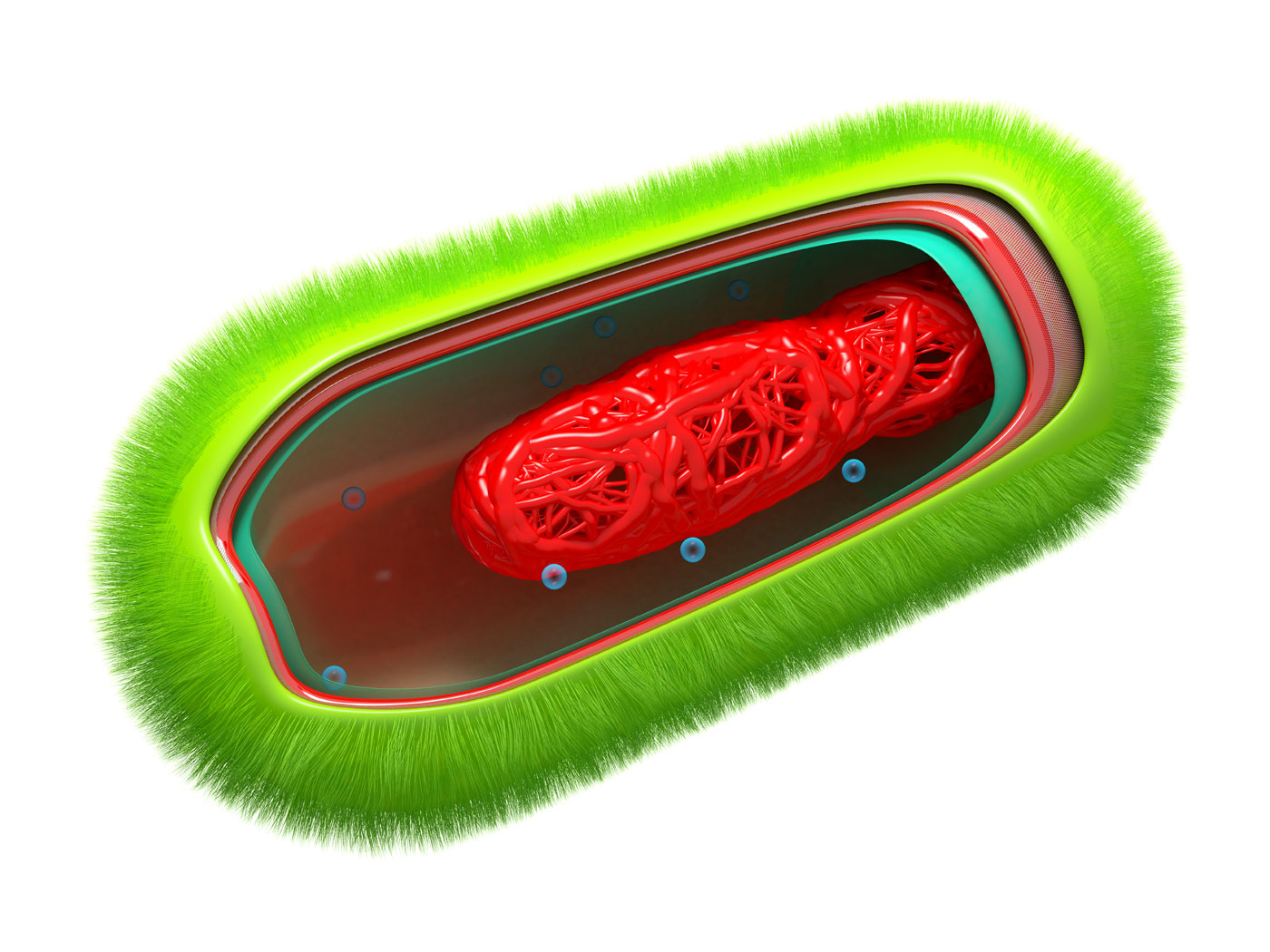

The assumptions about creatures made by an engineering-based approach are a radical about-face from selectionism’s. A TOBD is not only engineering-based, but it must also be organism-focused because of the way the engineering process works. Engineers produce designed entities and focus on them until they’re completed products (system, machine, etc.) with features operating within specified parameters. The capabilities the engineers design into the entity circumscribe all that it can/cannot do. In the biological sciences, creatures are those entities.

How does this influence how creatures are perceived? A TOBD assumes that any creature is a completed product. It assumes (with a super-accumulation of ongoing confirmatory observations) that its development, along with the myriad of systems and parts produced thereby, was purposeful and highly regulated. It predicts intricate and unified systems. It assumes that organisms will be active, problem-solving entities as they relate to their environment. The TOBD’s assumptions are far more likely to be accurate to reality and result in a high view of creatures and thus a high view of God.

Benefit 3: The Accuracy of Internalism Replaces Externalism

Internalism was the way researchers thought about how organisms worked prior to Darwin. He introduced a revolutionary perspective called externalism to interpret biological adaptation.5 The scientific view of creatures changed from their being designed to adjust themselves to fit changing environments to those environments slowly constructing them over time. As Harvard’s famed geneticist Richard Lewontin put it, “It is from this view of environment as the cause of organism that the entire corpus of modern biology arises.”6 The vocabulary and everything biology teaches is now wholly given over to externalism.

However, the organism-environment relationship can be extremely tight. How do you tease apart what’s causing what? It has always looked like environments change first and then organisms respond—though we now know of many exceptions.7 Selectionists describe ecology and geology as “driving” and “shaping” passive organisms, where exposures are depicted as “inducing” creatures and their sensors are pictured as “receptors.” A few lucky ones survive while most die out.

This overly simplistic and, thus, misleading narrative took hold because in Darwin’s day the way a creature adapted internally was a “black box” and out of view. But, there’s no reason to mistakenly see adaptation as externalistic today. Molecular biology reveals that masses of sensors and control systems innate to creatures regulate adaptation. An engineering approach shows that it was a huge mistake to see an event’s temporality as driving change and not the highly engineered innate biology that really produces the response.

Externalism is only a way of looking at creatures, but its influence cannot be overstated. When someone is trained to think within externalism as if it’s reality, it is exceedingly hard for them to look at creatures from the opposite perspective. That other perspective must involve more than seeing complexity in creatures or indicators of agency. Evolutionists recognize complexity and agency as well, but they chalk it up to their all-powerful selector, nature.

Instead, we need to change the way that we see how creatures themselves operate. Darwin taught us to see nature working on organisms. When we start seeing creatures work out of their engineered features and crediting those features in causal explanations, we’ll be thinking from a design perspective. The accuracy of internalism will return.

What It Means to Look at Organisms Within a TOBD

The internalistic perspective naturally focuses on organisms to explain their operation. Internalism seeks to answer the basic question “how?” Knowing how something works is the best way to move causal explanations from mysticism to objective reality.

Design engineering is fundamentally an internalistic activity. The basic design and potential modifications all focus on the designed entity to ensure that it will relate to the conditions it must operate in as purposed. Internalism is the basis for the objective, organism-focused way of seeing an organism as a distinct, engineered entity.

An internalistic approach fully understands that creatures work together, relate to external conditions, and sometimes suffer loss of control to, or absorption by, another organism. But in general when describing how two entities work together, they each control their own actions. Thus, internalism recognizes that what an organism can successfully accomplish is due to innate capabilities that must be present even for multi-organism experiences like cooperation, mutualism, or symbiosis.

The next step is to put internalism into practice. How do we begin to fundamentally look at creatures differently from an internalistic perspective within a TOBD? Besides abandoning selectionist verbiage, we think about a creature as an active, problem-solving agent instead of passive modeling clay.

First, we approach researching and describing the operation of a creature in the same way we would any intricate, human-engineered entity that must relate to wide-ranging external conditions. Second, if any underlying concepts or descriptions would sound silly when applied to the operation of man-made things, then we don’t apply them to biological things. Third, though nature is full of living things, it is not a living, thinking entity. Nature exists as a mindless, impartial, and unconscious temporal space.

Therefore, internalistic research programs, predictions, interpretations of biological observations, or causal explanations would be expressed within the context of the following assumptions.

- An organism’s biological functions are expected to operate through identifiable, innate, information-based control systems, which should be the principle focus in causal descriptions.

- The organism is the directing program for all purposeful outcomes and cannot be reduced below the level of self; e.g., DNA and its machinery are a subsystem of the organism.

- Goal-directed activity on an organism-wide basis is expected at every research level.

- Engineered, upfront capability is expected and investigated and should be the principle focus in causal explanations. Descriptions should emphasize that a) the organisms’ abilities to solve environmental challenges are not “due to” the challenge (selection pressure) but rather precede it; and b) any ability an organism has to adapt to, or learn from, experiences must be front-loaded since it cannot gain this ability through experience.

- An organism’s traits determine all of its capabilities. As in the descriptions of all engineered solutions, traits should be credited with the success of resolving an environmental challenge (i.e., this trait solved that challenge, not that it was “favored” by the environment).

- It’s a creature’s internal programming or traits that specify a) which conditions will be stimuli, b) which conditions are favorable or unfavorable, and c) which conditions will constitute its niche. Organisms relate to an identical condition differently based on their traits. Conditions are variables to which creatures are exposed, and a creature’s innate logic uses the variable data as an input to its programming to dictate its response. Organisms sense exposures and extract data; environments can’t “send instructions.” Exposures are not “drivers,” and no condition in-and-of-itself is a stimulus.

- The actual triggers initiating all self-adjustments by organisms are integrated sensors tuned to detect variable conditions. Thus, no condition in-and-of-itself is an inducer or trigger.

- Adaptation is the engineered control of the organism-environment relationship by the organism. Individuals and populations of organisms optimize the suitability of their traits to the environment through their innate, engineered control of the organism-environment relationship.

- Two independent entities will not “naturally” work together. Each must have an engineered system with an element that will connect to some characteristic of the other entity.

An engineering-based approach shows that switching perspectives is not simply a change in semantics. Consider the space shuttle Columbia, which suffered a heart-wrenching loss in 2003 while traversing the atmosphere on reentry. Any NASA engineer would lose his job if he explained that the heat-friction failure was because the shuttle wasn’t favored or the atmosphere selected against it.

The cause lay with the shuttle—not the atmosphere. The shuttle’s traits could be traced back to a specific engineering design, and thus design-based thinking could lead to tangible explanations for its performance. Engineers know that an entity’s traits determine all of its capabilities and should be identified with its success/failure of resolving environmental challenges.

The same is true for organisms. So, to look at creatures differently means to focus on their traits when thinking about how they work out their operation. When considering adaptation, look for all of the system elements (sensor/trigger, logic, etc.) that must exist between exposure and response.

There’s no magic; they have to be there. Dig into the scientific literature or do original research to identify them. Emphasize these traits when explaining how a creature self-adjusts to changed conditions. This is what it means to think from a design perspective in biology.

Conclusion

We need a conceptual catharsis of our understanding of how organisms relate to their environment. A TOBD offers objectivity, accuracy, and clarity of concepts and definitions with major benefits to biology. ICR’s recent Acts & Facts series on why biology needs a theory of biological design urges readers to open their minds, get current on the implications of today’s biological insights, and adopt a framework for interpreting biological observations that focuses on a creature’s innate capabilities and is guided by objective engineering principles.8

When researchers change the way they look at creatures, they’ll begin asking previously inconceivable questions, make new predictions, and, in essence, build different research programs. But most importantly, the new organism-focused emphasis in explanations offers a restored and profoundly nobler appreciation of the marvels engineered into creatures—and of their Creator, the Lord Jesus Christ.

Click here to read “Why Biology Needs A Theory of Biological Design, Part 1.”

Click here to read “Why Biology Needs A Theory of Biological Design, Part 2.”

Click here to read “Why Biology Needs A Theory of Biological Design, Part 3.”

References

- Joachim P. Sturmberg, “If You Change the Way You Look at Things, Things You Look at Change. Max Planck’s Challenge for Health, Health Care, and the Healthcare System,” in Embracing Complexity in Health: The Transformation of Science, Practice, and Policy, ed. Joachim P. Sturmberg (New York, NY: Springer, 2019), 3–44.

- Jerry Fodor and Massimo Piattelli-Palmarini, What Darwin Got Wrong (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010), 162–163.

- Neil Thomas, Taking Leave of Darwin: A Longtime Agnostic Discovers the Case for Design (Seattle, WA: Discovery Institute Press, 2021), 124.

- Charles Darwin, The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (London: John Murray, 1859), 429. Emphasis added.

- We previously detailed the history of externalism in Randy J. Guliuzza, “Engineered Adaptability: Adaptability Via Nature or Design? What Evolutionists Say,” Acts & Facts, September 2017, 17–19.

- Richard C. Lewontin, “Gene, Organism, and Environment,” in Evolution from Molecules to Man, ed. D. S. Bendall (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 274. Emphasis added.

- Randy J. Guliuzza, “Engineered Adaptability: Creatures’ Anticipatory Systems Forecast and Track Changes,” Acts & Facts, March 2019, 16–18.

- See the March/April, May/June, July/August, and September/October 2024 issues of Acts & Facts.

* Dr. Guliuzza is president of the Institute for Creation Research. He earned his doctor of medicine from the University of Minnesota, his master of public health from Harvard University, and received an honorary doctor of divinity from Southern California Seminary. He served in the U.S. Air Force as 28th Bomb Wing flight surgeon and chief of aerospace medicine. Dr. Guliuzza is also a registered professional engineer and holds a B.A. in theology from Moody Bible Institute.